The second part of Mexican architectural historian and professor Leonardo Díaz Borioli’s take on Trump’s border wall proposal, about Le Corbusier’s lessons as to the media, and why building such a wall by the letter would create a perverse architectural object. The first part is here.

Yours, you say, was an exercise to show how capable architecture is to start and literally shape a global political dialogue. But how do you start such a dialogue when the tone of the national conversation is set by populism, which by definition reduces concepts to their maximum simplification?

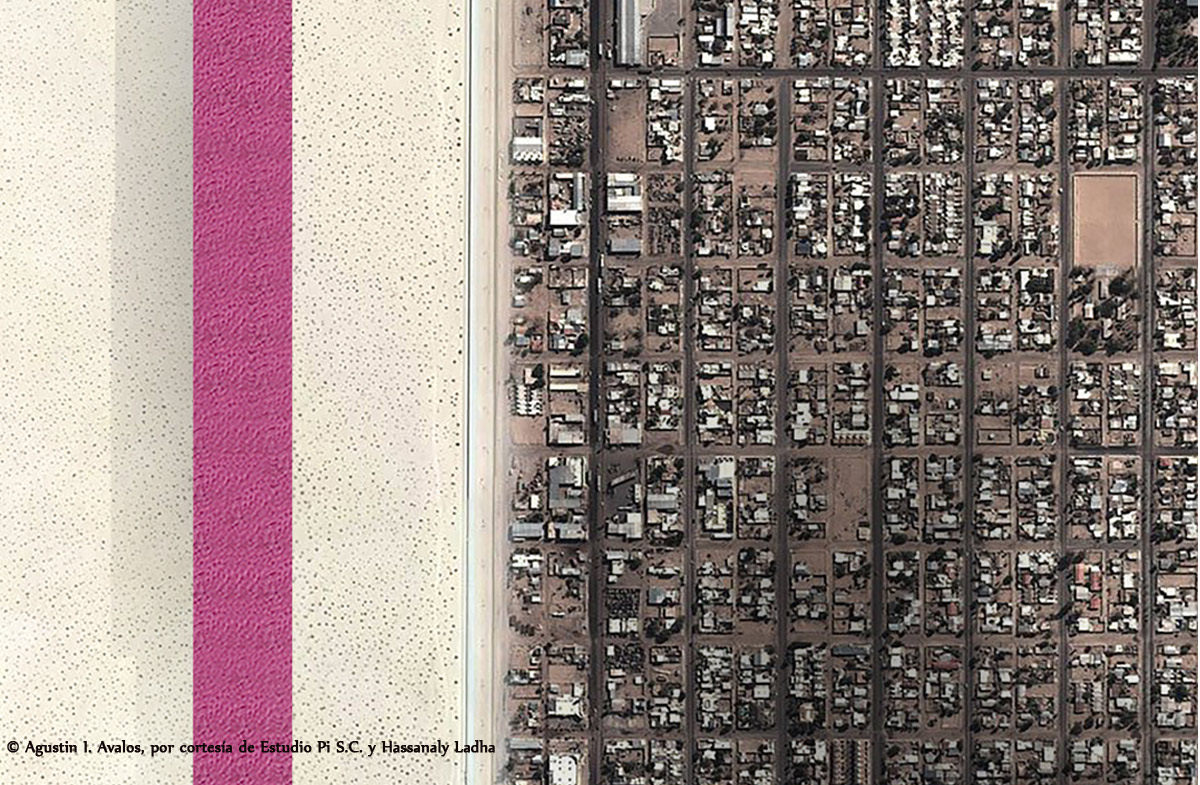

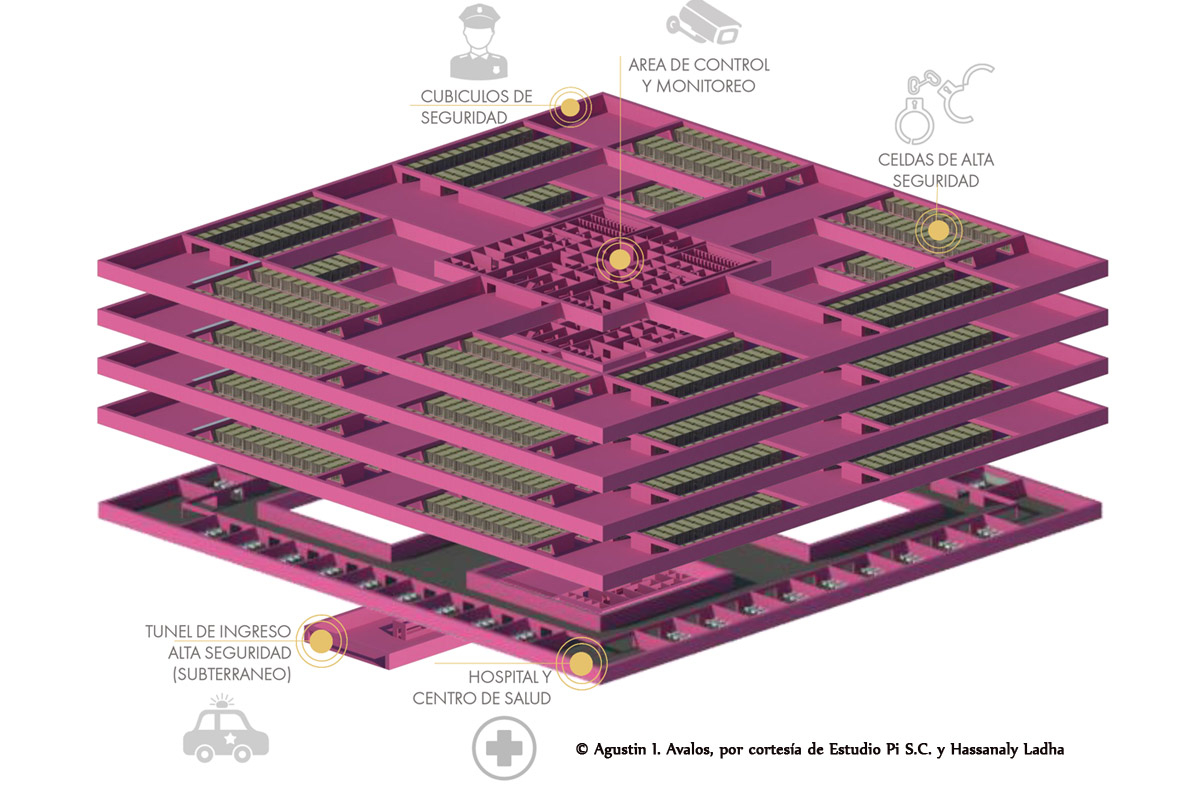

We went further along the lines of Mr. Trump’s aggressive logic, and placed the wall not on US territory but on Mexico’s side invoking an alleged agreement similar to the one regulating the Guantánamo prison. This means that, in our project, the prisoners deported from the US would not be protected by the US Constitution, and could therefore be subjected to forced labor in the maquilas [the factories that assemble products for US corporations, especially along the border, ed]. Their seized salaries would pay for the prison wall in 16 years, making it financially self-sufficient, which is the third element of Mr. Trump’s proposal. In other words, we created the most perverse architectural object in human history.

We went further along the lines of Mr. Trump’s aggressive logic, and placed the wall not on US territory but on Mexico’s side invoking an alleged agreement similar to the one regulating the Guantánamo prison. This means that, in our project, the prisoners deported from the US would not be protected by the US Constitution, and could therefore be subjected to forced labor in the maquilas [the factories that assemble products for US corporations, especially along the border, ed]. Their seized salaries would pay for the prison wall in 16 years, making it financially self-sufficient, which is the third element of Mr. Trump’s proposal. In other words, we created the most perverse architectural object in human history.

Some asked why the wall would be more perverse than Hitler’s crematoria, which were also architectural objects. Our response was that Hitler’s crematoria were not proposed to a democratic society to be voted upon. The fact that an object meant to cancel the lives of 11 million people and cause the death of the nation was chosen by a free and democratic society makes it much more perverse than the crematoria.

You achieved excellent results as to the dissemination of your project…

I mentioned the intersection between architecture and media, but with regard to this work, executed with the trainees of our study, we had not forecasted the success it reaped. Initially — that was before the election — we published it on some design and architecture websites, but in just 72 hours it had been published in five continents and six languages and more than 200 publications. Its impact on the media was huge. A short video was viewed 150,000 times, another one more than a million times. We had aimed at an architectural object that would formalize a political debate, but we had a surprise, rather than just achieving the results we expected. That made us realize the power of our project.

If architecture now becomes an element in national debates, in relation to which so far, apart from some controversies, it was relegated to specialized spheres, can we speak of a new role for architecture?

As a scholar I firmly believe there is an indication here for the need to change architecture curricula across the world. This a not new. The definition of modern architecture centered around Le Corbusier’s five points, the current one is that modern architecture begins with the encounter between architecture and the mass media, especially with photography around the 1920s. Another take-away is that what needs to be learned from Le Corbusier are not his five points, but his ingenuity as to the media. The problem is that even today, mass media are not taught in architecture schools, and so, yes, this is a new role. Architecture needs to wake up from its lethargy, and take ownership of the importance it had in the past, an importance passed as of lately to engineers, environmentalists and other professionals. Architects did not comprehend that the power of architecture now lies with the media, which are also a requisite in the practice of architecture.

So now we have, on the one hand, Mr. Trump’s architectural proposal along the lines of architecture’s oldest role, that is, asserting power through monumentality. On the other, you are assigning it a new major role as a communication medium. How do you to combine the two roles?

If architecture defines civilizations and today’s civilization is defined by social and mass media, what architecture must do now, on the wake of the tradition begun by Le Corbusier, is to combine the two and become a tool of a new symbolic reality that bears significance for civilization.

We hope that this experiment will prompt the deans of the schools of architecture all over the world to listen to their students, who are permanent communication and social media natives, and open up their curricula to these new possibilities for architecture. To keep it from dying out.