The CFO of Huawei, the world’s largest telco equipment maker, was arrested around a probe on US sanctions violations — just after Qualcomm announced Snapdragon 855, the chip that will power AI and 5G speeds– in your phone– a few months from now.

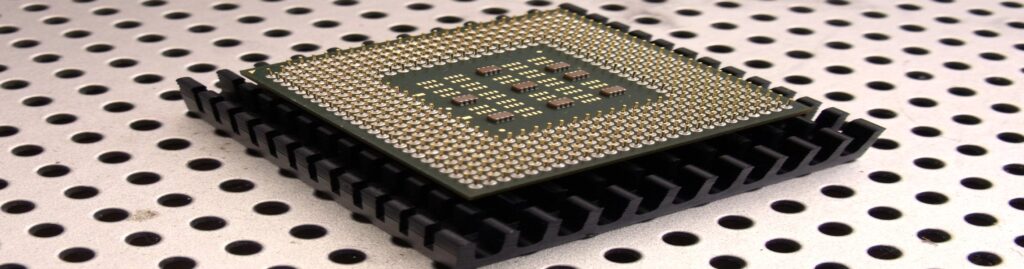

The link? Semiconductors are the new oil — and substituted oil as China’s Achilles’ heel. China is the largest consumer of semiconductors in the world, buying 45% of the global production (Huawei buys chips from Qualcomm and other American chip producers, although it now has the Kirin chips at the same level of performance). Of all the integrated circuits chips China’s huge manufacturing industry consumes, only a 16% is made in China. That is 16% of the $260 billion China spent last year on microchip imports, against the $162 billion that went on crude oil.

The stakes are very high: the tiny chips that act as the “brains” of all our devices, from smartphones and PCs to supercomputers, driverless transport, robotics and the Internet of Things (IoT) are also the building blocks of the technologies that will guarantee states their security and economic dominance in a not distant future: AI, machine learning (ML, its other form) and the low latency 5G networks with their potential to impact virtually all industries.

“Without advances in semiconductor process technology and chip design, on top of huge amounts of data and innovation in computing algorithms, AI could not have moved so rapidly from futuristic speculation to present-day reality,” reads a recent white paper of Semiconductors.org.

Semiconductors are critical in all three areas of a typical AI process flow — data generation through smartphones, automotive or multiple IoT devices; training of the AI/deep learning algorithms; and AI inference from real world use cases. Also ML requirements for computational power and chip memory are much higher than those for traditional programming and storage.

The worldwide semiconductor market is forecasted to be US$ 478 billion in 2018, an increase of 15.9% from 2017, and cool into 2019 though still to impressive $490 billion (a little less than a third of the global car market).

However, as Jack Ma, co-founder and ex-CEO of tech giant Alibaba, put it in Tokyo last April, “the market of chips is controlled by America… [what happens if] suddenly they stop selling”…? “Any country should have their own technology. A company should take responsibility for its customers, for the global future.”

Said and done, Alibaba recently acquired Chinese chipmaker C-SKY Microsystems to support its aggressive move into big data and AI and the development of smart chips for an IoT infrastructure and self-driving cars.

At any rate, Qualcomm is still by far the world leader in baseband chips for 4G and 5G communications technology, and patents, and gets from fast-growing brands like Huawei and Xiaomi fat royalties.

The rationale Qualcomm gave to explain why it was not interested anymore in acquiring Dutch chipmaker NXP should hence not come as a surprise. Qualcomm “is fully focused on continuing to execute on its 5G roadmap,” read keep its leadership in quality besides quantity.

China appears to be still a long way from having an influential market position as to quality and quantity in microchip production. It “is lagging behind global peers in terms of intellectual property portfolio and advanced technology development of integrated circuits (IC). The US’s IC design capability is still far ahead China’s (China does have Huawei but it’s only one company). Taiwan’s foundry is 5 years ahead of China’s. In IC assembly and packaging, China has stepped up to being a top 3 player globally,” said Kyna Wong, head of China Technology Research at Credit Suisse.

Establishing the National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, to channel cash to chip R&D, and the “Made in China 2025” program, designed to boost high-tech industries, Beijing set ambitious goals. It has pledged to meet 70% of domestic chip demand with homemade products in the next seven years (now at around 30%).

China is also brokering its way to these goals, like with the deal with British chip designer Arm, which ceded control of its Chinese operations to a local joint venture; or with the joint-venture Qualcomm entered with state-owned Datang Telco Technology to develop chips for cheap smartphones.

However, according to analysts, this does not solve the problem of intellectual property, which is paramount for the electronics manufacturing supply chain, besides paying lucrative royalties. The US earned $128 billion against outpayments of $48 billion in 2017. Vice-versa, China in 2016 earned just $1 billion and paid out $24 billion (probably quite less than it should have paid).

As Alibaba’s move would suggest, some observers, like China affairs veteran Tom Holland, believe that “China isn’t playing tech catch up (…) Beijing’s plans go far beyond import substitution: it plans to leapfrog the US and other Western economies to seize global dominance in a range of emerging technologies — and it may get dirty (…) In semiconductors, state planners want Chinese companies to command a third of the international market by 2030. And in artificial intelligence, they are aiming at nothing less than global dominance.”